The find command – search for files in a directory hierarchy. Here you can find some useful find command examples and manual guides. Follow the find command examples to learn Linux command line faster.

SYNOPSIS

find [-H] [-L] [-P] [-D debugopts] [-Olevel] [starting-point…] [expression]DESCRIPTION

This manual page documents the GNU version of find. GNU find searches the directory tree rooted at each given starting point by evaluating the given expression from left to right, according to the rules of precedence (see section OPERATORS), until the outcome is known (the left hand side is false for and operations, true for or), at which point find

moves on to the next file name. If no starting-point is specified, `.’ is assumed.

If you are using find in an environment where security is important (for example if you are using it to search directories that are writable by other users), you should read the `Security Considerations’ chapter of the findutils documentation, which is called Finding Files and comes with findutils. That document also includes a lot more detail and discussion than this manual page, so you may find it a more useful source of information.

OPTIONS

The -H, -L and -P options control the treatment of symbolic links. Command-line arguments following these are taken to be names of files or directories to be examined, up to the first argument that begins with -', or the argument(‘ or `!’. That argument and any following arguments are taken to be the expression describing what is to be searched for.

If no paths are given, the current directory is used. If no expression is given, the expression -print is used (but you should probably consider using -print0 instead, anyway).

This manual page talks about `options' within the expression list. These options control the behaviour of find but are specified immediately after the last path name. The five `real' options -H, -L, -P, -D and -O must appear before the first path name, if at all. A double dash -- can also be used to signal that any remaining arguments are not options (though ensuring that all start points begin with either `./' or `/' is generally safer if you use wildcards in the list of start points). -P Never follow symbolic links. This is the default behaviour. When find examines or prints information a file, and the file is a symbolic link, the information used shall be taken from the properties of the symbolic link it‐ self. -L Follow symbolic links. When find examines or prints information about files, the information used shall be taken from the properties of the file to which the link points, not from the link itself (unless it is a broken sym‐ bolic link or find is unable to examine the file to which the link points). Use of this option implies -noleaf. If you later use the -P option, -noleaf will still be in effect. If -L is in effect and find discovers a sym‐ bolic link to a subdirectory during its search, the subdirectory pointed to by the symbolic link will be searched. When the -L option is in effect, the -type predicate will always match against the type of the file that a sym‐ bolic link points to rather than the link itself (unless the symbolic link is broken). Actions that can cause symbolic links to become broken while find is executing (for example -delete) can give rise to confusing behav‐ iour. Using -L causes the -lname and -ilname predicates always to return false. -H Do not follow symbolic links, except while processing the command line arguments. When find examines or prints information about files, the information used shall be taken from the properties of the symbolic link itself. The only exception to this behaviour is when a file specified on the command line is a symbolic link, and the link can be resolved. For that situation, the information used is taken from whatever the link points to (that is, the link is followed). The information about the link itself is used as a fallback if the file pointed to by the symbolic link cannot be examined. If -H is in effect and one of the paths specified on the command line is a symbolic link to a directory, the contents of that directory will be examined (though of course -maxdepth 0 would prevent this). If more than one of -H, -L and -P is specified, each overrides the others; the last one appearing on the command line takes effect. Since it is the default, the -P option should be considered to be in effect unless either -H or -L is specified. GNU find frequently stats files during the processing of the command line itself, before any searching has begun. These options also affect how those arguments are processed. Specifically, there are a number of tests that compare files listed on the command line against a file we are currently considering. In each case, the file specified on the command line will have been examined and some of its properties will have been saved. If the named file is in fact a symbolic link, and the -P option is in effect (or if neither -H nor -L were specified), the information used for the comparison will be taken from the properties of the symbolic link. Otherwise, it will be taken from the properties of the file the link points to. If find cannot follow the link (for example because it has insufficient privileges or the link points to a nonexistent file) the properties of the link itself will be used. When the -H or -L options are in effect, any symbolic links listed as the argument of -newer will be dereferenced, and the timestamp will be taken from the file to which the symbolic link points. The same consideration applies to -new‐ erXY, -anewer and -cnewer. The -follow option has a similar effect to -L, though it takes effect at the point where it appears (that is, if -L is not used but -follow is, any symbolic links appearing after -follow on the command line will be dereferenced, and those before it will not). -D debugopts Print diagnostic information; this can be helpful to diagnose problems with why find is not doing what you want. The list of debug options should be comma separated. Compatibility of the debug options is not guaranteed be‐ tween releases of findutils. For a complete list of valid debug options, see the output of find -D help. Valid debug options include exec Show diagnostic information relating to -exec, -execdir, -ok and -okdir opt Prints diagnostic information relating to the optimisation of the expression tree; see the -O option. rates Prints a summary indicating how often each predicate succeeded or failed. search Navigate the directory tree verbosely. stat Print messages as files are examined with the stat and lstat system calls. The find program tries to min‐ imise such calls. tree Show the expression tree in its original and optimised form. all Enable all of the other debug options (but help). help Explain the debugging options. -Olevel Enables query optimisation. The find program reorders tests to speed up execution while preserving the overall effect; that is, predicates with side effects are not reordered relative to each other. The optimisations per‐ formed at each optimisation level are as follows. 0 Equivalent to optimisation level 1. 1 This is the default optimisation level and corresponds to the traditional behaviour. Expressions are re‐ ordered so that tests based only on the names of files (for example -name and -regex) are performed first. 2 Any -type or -xtype tests are performed after any tests based only on the names of files, but before any tests that require information from the inode. On many modern versions of Unix, file types are returned by readdir() and so these predicates are faster to evaluate than predicates which need to stat the file first. If you use the -fstype FOO predicate and specify a filesystem type FOO which is not known (that is, present in `/etc/mtab') at the time find starts, that predicate is equivalent to -false. 3 At this optimisation level, the full cost-based query optimiser is enabled. The order of tests is modi‐ fied so that cheap (i.e. fast) tests are performed first and more expensive ones are performed later, if necessary. Within each cost band, predicates are evaluated earlier or later according to whether they are likely to succeed or not. For -o, predicates which are likely to succeed are evaluated earlier, and for -a, predicates which are likely to fail are evaluated earlier. The cost-based optimiser has a fixed idea of how likely any given test is to succeed. In some cases the proba‐ bility takes account of the specific nature of the test (for example, -type f is assumed to be more likely to succeed than -type c). The cost-based optimiser is currently being evaluated. If it does not actually improve the performance of find, it will be removed again. Conversely, optimisations that prove to be reliable, robust and effective may be enabled at lower optimisation levels over time. However, the default behaviour (i.e. opti‐ misation level 1) will not be changed in the 4.3.x release series. The findutils test suite runs all the tests on find at each optimisation level and ensures that the result is the same.

EXPRESSION

The part of the command line after the list of starting points is the expression. This is a kind of query specification describing how we match files and what we do with the files that were matched. An expression is composed of a sequence of things:

Tests Tests return a true or false value, usually on the basis of some property of a file we are considering. The

-empty test for example is true only when the current file is empty.

Actions

Actions have side effects (such as printing something on the standard output) and return either true or false,

usually based on whether or not they are successful. The -print action for example prints the name of the cur‐

rent file on the standard output.

Global options

Global options affect the operation of tests and actions specified on any part of the command line. Global op‐

tions always return true. The -depth option for example makes find traverse the file system in a depth-first or‐

der.

Positional options

Positional options affect only tests or actions which follow them. Positional options always return true. The

-regextype option for example is positional, specifying the regular expression dialect for regular expressions

occurring later on the command line.

Operators

Operators join together the other items within the expression. They include for example -o (meaning logical OR)

and -a (meaning logical AND). Where an operator is missing, -a is assumed.

The -print action is performed on all files for which the whole expression is true, unless it contains an action other

than -prune or -quit. Actions which inhibit the default -print are -delete, -exec, -execdir, -ok, -okdir, -fls,

-fprint, -fprintf, -ls, -print and -printf.

The -delete action also acts like an option (since it implies -depth).POSITIONAL OPTIONS

Positional options always return true. They affect only tests occurring later on the command line.

-daystart

Measure times (for -amin, -atime, -cmin, -ctime, -mmin, and -mtime) from the beginning of today rather than from

24 hours ago. This option only affects tests which appear later on the command line.

-follow

Deprecated; use the -L option instead. Dereference symbolic links. Implies -noleaf. The -follow option affects

only those tests which appear after it on the command line. Unless the -H or -L option has been specified, the

position of the -follow option changes the behaviour of the -newer predicate; any files listed as the argument of

-newer will be dereferenced if they are symbolic links. The same consideration applies to -newerXY, -anewer and

-cnewer. Similarly, the -type predicate will always match against the type of the file that a symbolic link

points to rather than the link itself. Using -follow causes the -lname and -ilname predicates always to return

false.

-regextype type

Changes the regular expression syntax understood by -regex and -iregex tests which occur later on the command

line. To see which regular expression types are known, use -regextype help. The Texinfo documentation (see SEE

ALSO) explains the meaning of and differences between the various types of regular expression.

-warn, -nowarn

Turn warning messages on or off. These warnings apply only to the command line usage, not to any conditions that

find might encounter when it searches directories. The default behaviour corresponds to -warn if standard input

is a tty, and to -nowarn otherwise. If a warning message relating to command-line usage is produced, the exit

status of find is not affected. If the POSIXLY_CORRECT environment variable is set, and -warn is also used, it

is not specified which, if any, warnings will be active.GLOBAL OPTIONS

Global options always return true. Global options take effect even for tests which occur earlier on the command line. To prevent confusion, global options should specified on the command-line after the list of start points, just before the first test, positional option or action. If you specify a global option in some other place, find will issue a warning message explaining that this can be confusing.

The global options occur after the list of start points, and so are not the same kind of option as -L, for example.

-d A synonym for -depth, for compatibility with FreeBSD, NetBSD, MacOS X and OpenBSD.

-depth Process each directory's contents before the directory itself. The -delete action also implies -depth.

-help, --help

Print a summary of the command-line usage of find and exit.

-ignore_readdir_race

Normally, find will emit an error message when it fails to stat a file. If you give this option and a file is

deleted between the time find reads the name of the file from the directory and the time it tries to stat the

file, no error message will be issued. This also applies to files or directories whose names are given on the

command line. This option takes effect at the time the command line is read, which means that you cannot search

one part of the filesystem with this option on and part of it with this option off (if you need to do that, you

will need to issue two find commands instead, one with the option and one without it).

Furthermore, find with the -ignore_readdir_race option will ignore errors of the -delete action in the case the

file has disappeared since the parent directory was read: it will not output an error diagnostic, and the return

code of the -delete action will be true.

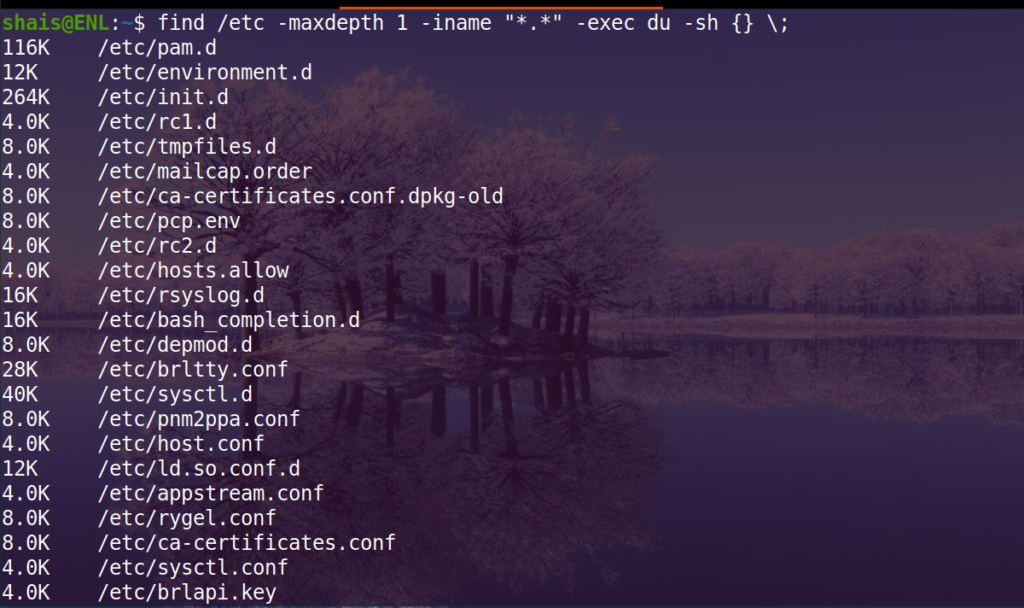

-maxdepth levels

Descend at most levels (a non-negative integer) levels of directories below the starting-points. -maxdepth 0

means only apply the tests and actions to the starting-points themselves.

-mindepth levels

Do not apply any tests or actions at levels less than levels (a non-negative integer). -mindepth 1 means process

all files except the starting-points.

-mount Don't descend directories on other filesystems. An alternate name for -xdev, for compatibility with some other

versions of find.

-noignore_readdir_race

Turns off the effect of -ignore_readdir_race.

-noleaf

Do not optimize by assuming that directories contain 2 fewer subdirectories than their hard link count. This op‐

tion is needed when searching filesystems that do not follow the Unix directory-link convention, such as CD-ROM

or MS-DOS filesystems or AFS volume mount points. Each directory on a normal Unix filesystem has at least 2 hard

links: its name and its `.' entry. Additionally, its subdirectories (if any) each have a `..' entry linked to

that directory. When find is examining a directory, after it has statted 2 fewer subdirectories than the direc‐

tory's link count, it knows that the rest of the entries in the directory are non-directories (`leaf' files in

the directory tree). If only the files' names need to be examined, there is no need to stat them; this gives a

significant increase in search speed.

-version, --version

Print the find version number and exit.

-xdev Don't descend directories on other filesystems.TESTS

Some tests, for example -newerXY and -samefile, allow comparison between the file currently being examined and some reference file specified on the command line. When these tests are used, the interpretation of the reference file is determined by the options -H, -L and -P and any previous -follow, but the reference file is only examined once, at the time the command line is parsed. If the reference file cannot be examined (for example, the stat(2) system call fails

for it), an error message is issued, and find exits with a nonzero status.

Numeric arguments can be specified as

+n for greater than n,

-n for less than n,

n for exactly n.

-amin n

File was last accessed n minutes ago.

-anewer reference

Time of the last access of the current file is more recent than that of the last data modification of the refer‐

ence file. If reference is a symbolic link and the -H option or the -L option is in effect, then the time of the

last data modification of the file it points to is always used.

-atime n

File was last accessed n*24 hours ago. When find figures out how many 24-hour periods ago the file was last ac‐

cessed, any fractional part is ignored, so to match -atime +1, a file has to have been accessed at least two days

ago.

-cmin n

File's status was last changed n minutes ago.

-cnewer reference

Time of the last status change of the current file is more recent than that of the last data modification of the

reference file. If reference is a symbolic link and the -H option or the -L option is in effect, then the time

of the last data modification of the file it points to is always used.

-ctime n

File's status was last changed n*24 hours ago. See the comments for -atime to understand how rounding affects

the interpretation of file status change times.

-empty File is empty and is either a regular file or a directory.

-executable

Matches files which are executable and directories which are searchable (in a file name resolution sense) by the

current user. This takes into account access control lists and other permissions artefacts which the -perm test

ignores. This test makes use of the access(2) system call, and so can be fooled by NFS servers which do UID map‐

ping (or root-squashing), since many systems implement access(2) in the client's kernel and so cannot make use of

the UID mapping information held on the server. Because this test is based only on the result of the access(2)

system call, there is no guarantee that a file for which this test succeeds can actually be executed.

-false Always false.

-fstype type

File is on a filesystem of type type. The valid filesystem types vary among different versions of Unix; an in‐

complete list of filesystem types that are accepted on some version of Unix or another is: ufs, 4.2, 4.3, nfs,

tmp, mfs, S51K, S52K. You can use -printf with the %F directive to see the types of your filesystems.

-gid n File's numeric group ID is n.

-group gname

File belongs to group gname (numeric group ID allowed).

-ilname pattern

Like -lname, but the match is case insensitive. If the -L option or the -follow option is in effect, this test

returns false unless the symbolic link is broken.

-iname pattern

Like -name, but the match is case insensitive. For example, the patterns `fo*' and `F??' match the file names

`Foo', `FOO', `foo', `fOo', etc. The pattern `*foo*` will also match a file called '.foobar'.

-inum n

File has inode number n. It is normally easier to use the -samefile test instead.

-ipath pattern

Like -path. but the match is case insensitive.

-iregex pattern

Like -regex, but the match is case insensitive.

-iwholename pattern

See -ipath. This alternative is less portable than -ipath.

-links n

File has n hard links.

-lname pattern

File is a symbolic link whose contents match shell pattern pattern. The metacharacters do not treat `/' or `.'

specially. If the -L option or the -follow option is in effect, this test returns false unless the symbolic link

is broken.

-mmin n

File's data was last modified n minutes ago.

-mtime n

File's data was last modified n*24 hours ago. See the comments for -atime to understand how rounding affects the

interpretation of file modification times.

-name pattern

Base of file name (the path with the leading directories removed) matches shell pattern pattern. Because the

leading directories are removed, the file names considered for a match with -name will never include a slash, so

`-name a/b' will never match anything (you probably need to use -path instead). A warning is issued if you try

to do this, unless the environment variable POSIXLY_CORRECT is set. The metacharacters (`*', `?', and `[]')

match a `.' at the start of the base name (this is a change in findutils-4.2.2; see section STANDARDS CONFORMANCE

below). To ignore a directory and the files under it, use -prune rather than checking every file in the tree;

see an example in the description of that action. Braces are not recognised as being special, despite the fact

that some shells including Bash imbue braces with a special meaning in shell patterns. The filename matching is

performed with the use of the fnmatch(3) library function. Don't forget to enclose the pattern in quotes in or‐

der to protect it from expansion by the shell.

-newer reference

Time of the last data modification of the current file is more recent than that of the last data modification of

the reference file. If reference is a symbolic link and the -H option or the -L option is in effect, then the

time of the last data modification of the file it points to is always used.

-newerXY reference

Succeeds if timestamp X of the file being considered is newer than timestamp Y of the file reference. The let‐

ters X and Y can be any of the following letters:

a The access time of the file reference

B The birth time of the file reference

c The inode status change time of reference

m The modification time of the file reference

t reference is interpreted directly as a time

Some combinations are invalid; for example, it is invalid for X to be t. Some combinations are not implemented

on all systems; for example B is not supported on all systems. If an invalid or unsupported combination of XY is

specified, a fatal error results. Time specifications are interpreted as for the argument to the -d option of

GNU date. If you try to use the birth time of a reference file, and the birth time cannot be determined, a fatal

error message results. If you specify a test which refers to the birth time of files being examined, this test

will fail for any files where the birth time is unknown.

-nogroup

No group corresponds to file's numeric group ID.

-nouser

No user corresponds to file's numeric user ID.

-path pattern

File name matches shell pattern pattern. The metacharacters do not treat `/' or `.' specially; so, for example,

find . -path "./sr*sc"

will print an entry for a directory called `./src/misc' (if one exists). To ignore a whole directory tree, use

-prune rather than checking every file in the tree. Note that the pattern match test applies to the whole file

name, starting from one of the start points named on the command line. It would only make sense to use an abso‐

lute path name here if the relevant start point is also an absolute path. This means that this command will

never match anything:

find bar -path /foo/bar/myfile -print

Find compares the -path argument with the concatenation of a directory name and the base name of the file it's

examining. Since the concatenation will never end with a slash, -path arguments ending in a slash will match

nothing (except perhaps a start point specified on the command line). The predicate -path is also supported by

HP-UX find and is part of the POSIX 2008 standard.

-perm mode

File's permission bits are exactly mode (octal or symbolic). Since an exact match is required, if you want to

use this form for symbolic modes, you may have to specify a rather complex mode string. For example `-perm g=w'

will only match files which have mode 0020 (that is, ones for which group write permission is the only permission

set). It is more likely that you will want to use the `/' or `-' forms, for example `-perm -g=w', which matches

any file with group write permission. See the EXAMPLES section for some illustrative examples.

-perm -mode

All of the permission bits mode are set for the file. Symbolic modes are accepted in this form, and this is usu‐

ally the way in which you would want to use them. You must specify `u', `g' or `o' if you use a symbolic mode.

See the EXAMPLES section for some illustrative examples.

-perm /mode

Any of the permission bits mode are set for the file. Symbolic modes are accepted in this form. You must spec‐

ify `u', `g' or `o' if you use a symbolic mode. See the EXAMPLES section for some illustrative examples. If no

permission bits in mode are set, this test matches any file (the idea here is to be consistent with the behaviour

of -perm -000).

-perm +mode

This is no longer supported (and has been deprecated since 2005). Use -perm /mode instead.

-readable

Matches files which are readable by the current user. This takes into account access control lists and other

permissions artefacts which the -perm test ignores. This test makes use of the access(2) system call, and so can

be fooled by NFS servers which do UID mapping (or root-squashing), since many systems implement access(2) in the

client's kernel and so cannot make use of the UID mapping information held on the server.

-regex pattern

File name matches regular expression pattern. This is a match on the whole path, not a search. For example, to

match a file named `./fubar3', you can use the regular expression `.*bar.' or `.*b.*3', but not `f.*r3'. The

regular expressions understood by find are by default Emacs Regular Expressions (except that `.' matches new‐

line), but this can be changed with the -regextype option.

-samefile name

File refers to the same inode as name. When -L is in effect, this can include symbolic links.

-size n[cwbkMG]

File uses n units of space, rounding up. The following suffixes can be used:

`b' for 512-byte blocks (this is the default if no suffix is used)

`c' for bytes

`w' for two-byte words

`k' for kibibytes (KiB, units of 1024 bytes)

`M' for mebibytes (MiB, units of 1024 * 1024 = 1048576 bytes)

`G' for gibibytes (GiB, units of 1024 * 1024 * 1024 = 1073741824 bytes)

The size is simply the st_size member of the struct stat populated by the lstat (or stat) system call, rounded up

as shown above. In other words, it's consistent with the result you get for ls -l. Bear in mind that the `%k'

and `%b' format specifiers of -printf handle sparse files differently. The `b' suffix always denotes 512-byte

blocks and never 1024-byte blocks, which is different to the behaviour of -ls.

The + and - prefixes signify greater than and less than, as usual; i.e., an exact size of n units does not match.

Bear in mind that the size is rounded up to the next unit. Therefore -size -1M is not equivalent to -size

-1048576c. The former only matches empty files, the latter matches files from 0 to 1,048,575 bytes.

-true Always true.

-type c

File is of type c:

b block (buffered) special

c character (unbuffered) special

d directory

p named pipe (FIFO)

f regular file

l symbolic link; this is never true if the -L option or the -follow option is in effect, unless the symbolic

link is broken. If you want to search for symbolic links when -L is in effect, use -xtype.

s socket

D door (Solaris)

To search for more than one type at once, you can supply the combined list of type letters separated by a comma

`,' (GNU extension).

-uid n File's numeric user ID is n.

-used n

File was last accessed n days after its status was last changed.

-user uname

File is owned by user uname (numeric user ID allowed).

-wholename pattern

See -path. This alternative is less portable than -path.

-writable

Matches files which are writable by the current user. This takes into account access control lists and other

permissions artefacts which the -perm test ignores. This test makes use of the access(2) system call, and so can

be fooled by NFS servers which do UID mapping (or root-squashing), since many systems implement access(2) in the

client's kernel and so cannot make use of the UID mapping information held on the server.

-xtype c

The same as -type unless the file is a symbolic link. For symbolic links: if the -H or -P option was specified,

true if the file is a link to a file of type c; if the -L option has been given, true if c is `l'. In other

words, for symbolic links, -xtype checks the type of the file that -type does not check.

-context pattern

(SELinux only) Security context of the file matches glob pattern.ACTIONS

-deleteDelete files; true if removal succeeded. If the removal failed, an error message is issued. If delete fails, find’s exit status will be nonzero (when it eventually exits). Use of -delete automatically turns on the `-depth’ option.

Warnings: Don’t forget that the find command line is evaluated as an expression, so putting -delete first will make find try to delete everything below the starting points you specified. When testing a find command line that you later intend to use with -delete, you should explicitly specify -depth in order to avoid later surprises. Because -delete implies -depth, you cannot usefully use -prune and -delete together.

Together with the -ignore_readdir_race option, find will ignore errors of the -delete action in the case the file has disappeared since the parent directory was read: it will not output an error diagnostic, and the return code of the -delete action will be true.

-exec command ;

Execute command; true if 0 status is returned. All following arguments to find are taken to be arguments to the

command until an argument consisting of `;' is encountered. The string `{}' is replaced by the current file name

being processed everywhere it occurs in the arguments to the command, not just in arguments where it is alone, as

in some versions of find. Both of these constructions might need to be escaped (with a `\') or quoted to protect

them from expansion by the shell. See the EXAMPLES section for examples of the use of the -exec option. The

specified command is run once for each matched file. The command is executed in the starting directory. There

are unavoidable security problems surrounding use of the -exec action; you should use the -execdir option in‐

stead.

-exec command {} +

This variant of the -exec action runs the specified command on the selected files, but the command line is built

by appending each selected file name at the end; the total number of invocations of the command will be much less

than the number of matched files. The command line is built in much the same way that xargs builds its command

lines. Only one instance of `{}' is allowed within the command, and (when find is being invoked from a shell) it

should be quoted (for example, '{}') to protect it from interpretation by shells. The command is executed in the

starting directory. If any invocation with the `+' form returns a non-zero value as exit status, then find re‐

turns a non-zero exit status. If find encounters an error, this can sometimes cause an immediate exit, so some

pending commands may not be run at all. This variant of -exec always returns true.

-execdir command ;

-execdir command {} +

Like -exec, but the specified command is run from the subdirectory containing the matched file, which is not nor‐

mally the directory in which you started find. As with -exec, the {} should be quoted if find is being invoked

from a shell. This a much more secure method for invoking commands, as it avoids race conditions during resolu‐

tion of the paths to the matched files. As with the -exec action, the `+' form of -execdir will build a command

line to process more than one matched file, but any given invocation of command will only list files that exist

in the same subdirectory. If you use this option, you must ensure that your $PATH environment variable does not

reference `.'; otherwise, an attacker can run any commands they like by leaving an appropriately-named file in a

directory in which you will run -execdir. The same applies to having entries in $PATH which are empty or which

are not absolute directory names. If any invocation with the `+' form returns a non-zero value as exit status,

then find returns a non-zero exit status. If find encounters an error, this can sometimes cause an immediate

exit, so some pending commands may not be run at all. The result of the action depends on whether the + or the ;

variant is being used; -execdir command {} + always returns true, while -execdir command {} ; returns true only

if command returns 0.

-fls file

True; like -ls but write to file like -fprint. The output file is always created, even if the predicate is never

matched. See the UNUSUAL FILENAMES section for information about how unusual characters in filenames are han‐

dled.

-fprint file

True; print the full file name into file file. If file does not exist when find is run, it is created; if it

does exist, it is truncated. The file names `/dev/stdout' and `/dev/stderr' are handled specially; they refer to

the standard output and standard error output, respectively. The output file is always created, even if the

predicate is never matched. See the UNUSUAL FILENAMES section for information about how unusual characters in

filenames are handled.

-fprint0 file

True; like -print0 but write to file like -fprint. The output file is always created, even if the predicate is

never matched. See the UNUSUAL FILENAMES section for information about how unusual characters in filenames are

handled.

-fprintf file format

True; like -printf but write to file like -fprint. The output file is always created, even if the predicate is

never matched. See the UNUSUAL FILENAMES section for information about how unusual characters in filenames are

handled.

-ls True; list current file in ls -dils format on standard output. The block counts are of 1 KB blocks, unless the

environment variable POSIXLY_CORRECT is set, in which case 512-byte blocks are used. See the UNUSUAL FILENAMES

section for information about how unusual characters in filenames are handled.

-ok command ;

Like -exec but ask the user first. If the user agrees, run the command. Otherwise just return false. If the

command is run, its standard input is redirected from /dev/null.

The response to the prompt is matched against a pair of regular expressions to determine if it is an affirmative

or negative response. This regular expression is obtained from the system if the `POSIXLY_CORRECT' environment

variable is set, or otherwise from find's message translations. If the system has no suitable definition, find's

own definition will be used. In either case, the interpretation of the regular expression itself will be af‐

fected by the environment variables 'LC_CTYPE' (character classes) and 'LC_COLLATE' (character ranges and equiva‐

lence classes).

-okdir command ;

Like -execdir but ask the user first in the same way as for -ok. If the user does not agree, just return false.

If the command is run, its standard input is redirected from /dev/null.

-print True; print the full file name on the standard output, followed by a newline. If you are piping the output of

find into another program and there is the faintest possibility that the files which you are searching for might

contain a newline, then you should seriously consider using the -print0 option instead of -print. See the UN‐

USUAL FILENAMES section for information about how unusual characters in filenames are handled.

-print0

True; print the full file name on the standard output, followed by a null character (instead of the newline char‐

acter that -print uses). This allows file names that contain newlines or other types of white space to be cor‐

rectly interpreted by programs that process the find output. This option corresponds to the -0 option of xargs.

-printf format

True; print format on the standard output, interpreting `\' escapes and `%' directives. Field widths and preci‐

sions can be specified as with the `printf' C function. Please note that many of the fields are printed as %s

rather than %d, and this may mean that flags don't work as you might expect. This also means that the `-' flag

does work (it forces fields to be left-aligned). Unlike -print, -printf does not add a newline at the end of the

string. The escapes and directives are:

\a Alarm bell.

\b Backspace.

\c Stop printing from this format immediately and flush the output.

\f Form feed.

\n Newline.

\r Carriage return.

\t Horizontal tab.

\v Vertical tab.

\0 ASCII NUL.

\\ A literal backslash (`\').

\NNN The character whose ASCII code is NNN (octal).

A `\' character followed by any other character is treated as an ordinary character, so they both are printed.

%% A literal percent sign.

%a File's last access time in the format returned by the C `ctime' function.

%Ak File's last access time in the format specified by k, which is either `@' or a directive for the C `strf‐

time' function. The possible values for k are listed below; some of them might not be available on all

systems, due to differences in `strftime' between systems.

@ seconds since Jan. 1, 1970, 00:00 GMT, with fractional part.

Time fields:

H hour (00..23)

I hour (01..12)

k hour ( 0..23)

l hour ( 1..12)

M minute (00..59)

p locale's AM or PM

r time, 12-hour (hh:mm:ss [AP]M)

S Second (00.00 .. 61.00). There is a fractional part.

T time, 24-hour (hh:mm:ss.xxxxxxxxxx)

+ Date and time, separated by `+', for example `2004-04-28+22:22:05.0'. This is a GNU extension.

The time is given in the current timezone (which may be affected by setting the TZ environment

variable). The seconds field includes a fractional part.

X locale's time representation (H:M:S). The seconds field includes a fractional part.

Z time zone (e.g., EDT), or nothing if no time zone is determinable

Date fields:

a locale's abbreviated weekday name (Sun..Sat)

A locale's full weekday name, variable length (Sunday..Saturday)

b locale's abbreviated month name (Jan..Dec)

B locale's full month name, variable length (January..December)

c locale's date and time (Sat Nov 04 12:02:33 EST 1989). The format is the same as for ctime(3) and

so to preserve compatibility with that format, there is no fractional part in the seconds field.

d day of month (01..31)

D date (mm/dd/yy)

h same as b

j day of year (001..366)

m month (01..12)

U week number of year with Sunday as first day of week (00..53)

w day of week (0..6)

W week number of year with Monday as first day of week (00..53)

x locale's date representation (mm/dd/yy)

y last two digits of year (00..99)

Y year (1970...)

%b The amount of disk space used for this file in 512-byte blocks. Since disk space is allocated in multi‐

ples of the filesystem block size this is usually greater than %s/512, but it can also be smaller if the

file is a sparse file.

%c File's last status change time in the format returned by the C `ctime' function.

%Ck File's last status change time in the format specified by k, which is the same as for %A.

%d File's depth in the directory tree; 0 means the file is a starting-point.

%D The device number on which the file exists (the st_dev field of struct stat), in decimal.

%f File's name with any leading directories removed (only the last element).

%F Type of the filesystem the file is on; this value can be used for -fstype.

%g File's group name, or numeric group ID if the group has no name.

%G File's numeric group ID.

%h Leading directories of file's name (all but the last element). If the file name contains no slashes

(since it is in the current directory) the %h specifier expands to `.'.

%H Starting-point under which file was found.

%i File's inode number (in decimal).

%k The amount of disk space used for this file in 1 KB blocks. Since disk space is allocated in multiples of

the filesystem block size this is usually greater than %s/1024, but it can also be smaller if the file is

a sparse file.

%l Object of symbolic link (empty string if file is not a symbolic link).

%m File's permission bits (in octal). This option uses the `traditional' numbers which most Unix implementa‐

tions use, but if your particular implementation uses an unusual ordering of octal permissions bits, you

will see a difference between the actual value of the file's mode and the output of %m. Normally you will

want to have a leading zero on this number, and to do this, you should use the # flag (as in, for example,

`%#m').

%M File's permissions (in symbolic form, as for ls). This directive is supported in findutils 4.2.5 and

later.

%n Number of hard links to file.

%p File's name.

%P File's name with the name of the starting-point under which it was found removed.

%s File's size in bytes.

%S File's sparseness. This is calculated as (BLOCKSIZE*st_blocks / st_size). The exact value you will get

for an ordinary file of a certain length is system-dependent. However, normally sparse files will have

values less than 1.0, and files which use indirect blocks may have a value which is greater than 1.0. In

general the number of blocks used by a file is file system dependent. The value used for BLOCKSIZE is

system-dependent, but is usually 512 bytes. If the file size is zero, the value printed is undefined. On

systems which lack support for st_blocks, a file's sparseness is assumed to be 1.0.

%t File's last modification time in the format returned by the C `ctime' function.

%Tk File's last modification time in the format specified by k, which is the same as for %A.

%u File's user name, or numeric user ID if the user has no name.

%U File's numeric user ID.

%y File's type (like in ls -l), U=unknown type (shouldn't happen)

%Y File's type (like %y), plus follow symlinks: `L'=loop, `N'=nonexistent, `?' for any other error when de‐

termining the type of the symlink target.

%Z (SELinux only) file's security context.

%{ %[ %(

Reserved for future use.

A `%' character followed by any other character is discarded, but the other character is printed (don't rely on

this, as further format characters may be introduced). A `%' at the end of the format argument causes undefined

behaviour since there is no following character. In some locales, it may hide your door keys, while in others it

may remove the final page from the novel you are reading.

The %m and %d directives support the # , 0 and + flags, but the other directives do not, even if they print num‐

bers. Numeric directives that do not support these flags include G, U, b, D, k and n. The `-' format flag is

supported and changes the alignment of a field from right-justified (which is the default) to left-justified.

See the UNUSUAL FILENAMES section for information about how unusual characters in filenames are handled.

-prune True; if the file is a directory, do not descend into it. If -depth is given, then -prune has no effect. Be‐

cause -delete implies -depth, you cannot usefully use -prune and -delete together.

For example, to skip the directory `src/emacs' and all files and directories under it, and print the names of

the other files found, do something like this:

find . -path ./src/emacs -prune -o -print

-quit Exit immediately. No child processes will be left running, but no more paths specified on the command line will

be processed. For example, find /tmp/foo /tmp/bar -print -quit will print only /tmp/foo. Any command lines

which have been built up with -execdir ... {} + will be invoked before find exits. The exit status may or may

not be zero, depending on whether an error has already occurred.OPERATORS

Listed in order of decreasing precedence:

( expr )

Force precedence. Since parentheses are special to the shell, you will normally need to quote them. Many of the

examples in this manual page use backslashes for this purpose: `\(...\)' instead of `(...)'.

! expr True if expr is false. This character will also usually need protection from interpretation by the shell.

-not expr

Same as ! expr, but not POSIX compliant.

expr1 expr2

Two expressions in a row are taken to be joined with an implied -a; expr2 is not evaluated if expr1 is false.

expr1 -a expr2

Same as expr1 expr2.

expr1 -and expr2

Same as expr1 expr2, but not POSIX compliant.

expr1 -o expr2

Or; expr2 is not evaluated if expr1 is true.

expr1 -or expr2

Same as expr1 -o expr2, but not POSIX compliant.

expr1 , expr2

List; both expr1 and expr2 are always evaluated. The value of expr1 is discarded; the value of the list is the

value of expr2. The comma operator can be useful for searching for several different types of thing, but

traversing the filesystem hierarchy only once. The -fprintf action can be used to list the various matched items

into several different output files.

Please note that -a when specified implicitly (for example by two tests appearing without an explicit operator between

them) or explicitly has higher precedence than -o. This means that find . -name afile -o -name bfile -print will never

print afile.UNUSUAL FILENAMES

Many of the actions of find result in the printing of data which is under the control of other users. This includes file names, sizes, modification times and so forth. File names are a potential problem since they can contain any character except \0' and/’. Unusual characters in file names can do unexpected and often undesirable things to your terminal (for example, changing the settings of your function keys on some terminals). Unusual characters are handled differently by various actions, as described below.

-print0, -fprint0

Always print the exact filename, unchanged, even if the output is going to a terminal.

-ls, -fls

Unusual characters are always escaped. White space, backslash, and double quote characters are printed using C-

style escaping (for example `\f', `\"'). Other unusual characters are printed using an octal escape. Other

printable characters (for -ls and -fls these are the characters between octal 041 and 0176) are printed as-is.

-printf, -fprintf

If the output is not going to a terminal, it is printed as-is. Otherwise, the result depends on which directive

is in use. The directives %D, %F, %g, %G, %H, %Y, and %y expand to values which are not under control of files'

owners, and so are printed as-is. The directives %a, %b, %c, %d, %i, %k, %m, %M, %n, %s, %t, %u and %U have val‐

ues which are under the control of files' owners but which cannot be used to send arbitrary data to the terminal,

and so these are printed as-is. The directives %f, %h, %l, %p and %P are quoted. This quoting is performed in

the same way as for GNU ls. This is not the same quoting mechanism as the one used for -ls and -fls. If you are

able to decide what format to use for the output of find then it is normally better to use `\0' as a terminator

than to use newline, as file names can contain white space and newline characters. The setting of the `LC_CTYPE'

environment variable is used to determine which characters need to be quoted.

-print, -fprint

Quoting is handled in the same way as for -printf and -fprintf. If you are using find in a script or in a situa‐

tion where the matched files might have arbitrary names, you should consider using -print0 instead of -print.

The -ok and -okdir actions print the current filename as-is. This may change in a future release.STANDARDS CONFORMANCE

For closest compliance to the POSIX standard, you should set the POSIXLY_CORRECT environment variable. The following options are specified in the POSIX standard (IEEE Std 1003.1-2008, 2016 Edition):

-H This option is supported.

-L This option is supported.

-name This option is supported, but POSIX conformance depends on the POSIX conformance of the system's fnmatch(3) li‐

brary function. As of findutils-4.2.2, shell metacharacters (`*', `?' or `[]' for example) will match a leading

`.', because IEEE PASC interpretation 126 requires this. This is a change from previous versions of findutils.

-type Supported. POSIX specifies `b', `c', `d', `l', `p', `f' and `s'. GNU find also supports `D', representing a

Door, where the OS provides these. Furthermore, GNU find allows multiple types to be specified at once in a

comma-separated list.

-ok Supported. Interpretation of the response is according to the `yes' and `no' patterns selected by setting the

`LC_MESSAGES' environment variable. When the `POSIXLY_CORRECT' environment variable is set, these patterns are

taken system's definition of a positive (yes) or negative (no) response. See the system's documentation for

nl_langinfo(3), in particular YESEXPR and NOEXPR. When `POSIXLY_CORRECT' is not set, the patterns are instead

taken from find's own message catalogue.

-newer Supported. If the file specified is a symbolic link, it is always dereferenced. This is a change from previous

behaviour, which used to take the relevant time from the symbolic link; see the HISTORY section below.

-perm Supported. If the POSIXLY_CORRECT environment variable is not set, some mode arguments (for example +a+x) which

are not valid in POSIX are supported for backward-compatibility.

Other primaries

The primaries -atime, -ctime, -depth, -exec, -group, -links, -mtime, -nogroup, -nouser, -ok, -path, -print,

-prune, -size, -user and -xdev are all supported.

The POSIX standard specifies parentheses `(', `)', negation `!' and the `and' and `or' operators ( -a, -o).

All other options, predicates, expressions and so forth are extensions beyond the POSIX standard. Many of these exten‐

sions are not unique to GNU find, however.

The POSIX standard requires that find detects loops:

The find utility shall detect infinite loops; that is, entering a previously visited directory that is an ances‐

tor of the last file encountered. When it detects an infinite loop, find shall write a diagnostic message to

standard error and shall either recover its position in the hierarchy or terminate.

GNU find complies with these requirements. The link count of directories which contain entries which are hard links to

an ancestor will often be lower than they otherwise should be. This can mean that GNU find will sometimes optimise away

the visiting of a subdirectory which is actually a link to an ancestor. Since find does not actually enter such a sub‐

directory, it is allowed to avoid emitting a diagnostic message. Although this behaviour may be somewhat confusing, it

is unlikely that anybody actually depends on this behaviour. If the leaf optimisation has been turned off with -noleaf,

the directory entry will always be examined and the diagnostic message will be issued where it is appropriate. Symbolic

links cannot be used to create filesystem cycles as such, but if the -L option or the -follow option is in use, a diag‐

nostic message is issued when find encounters a loop of symbolic links. As with loops containing hard links, the leaf

optimisation will often mean that find knows that it doesn't need to call stat() or chdir() on the symbolic link, so

this diagnostic is frequently not necessary.

The -d option is supported for compatibility with various BSD systems, but you should use the POSIX-compliant option

-depth instead.

The POSIXLY_CORRECT environment variable does not affect the behaviour of the -regex or -iregex tests because those

tests aren't specified in the POSIX standard.ENVIRONMENT VARIABLES

LANG Provides a default value for the internationalisation variables that are unset or null.

LC_ALL If set to a non-empty string value, override the values of all the other internationalization variables.

LC_COLLATE

The POSIX standard specifies that this variable affects the pattern matching to be used for the -name option.

GNU find uses the fnmatch(3) library function, and so support for `LC_COLLATE' depends on the system library.

This variable also affects the interpretation of the response to -ok; while the `LC_MESSAGES' variable selects

the actual pattern used to interpret the response to -ok, the interpretation of any bracket expressions in the

pattern will be affected by `LC_COLLATE'.

LC_CTYPE

This variable affects the treatment of character classes used in regular expressions and also with the -name

test, if the system's fnmatch(3) library function supports this. This variable also affects the interpretation

of any character classes in the regular expressions used to interpret the response to the prompt issued by -ok.

The `LC_CTYPE' environment variable will also affect which characters are considered to be unprintable when file‐

names are printed; see the section UNUSUAL FILENAMES.

LC_MESSAGES

Determines the locale to be used for internationalised messages. If the `POSIXLY_CORRECT' environment variable

is set, this also determines the interpretation of the response to the prompt made by the -ok action.

NLSPATH

Determines the location of the internationalisation message catalogues.

PATH Affects the directories which are searched to find the executables invoked by -exec, -execdir, -ok and -okdir.

POSIXLY_CORRECT

Determines the block size used by -ls and -fls. If POSIXLY_CORRECT is set, blocks are units of 512 bytes. Oth‐

erwise they are units of 1024 bytes.

Setting this variable also turns off warning messages (that is, implies -nowarn) by default, because POSIX re‐

quires that apart from the output for -ok, all messages printed on stderr are diagnostics and must result in a

non-zero exit status.

When POSIXLY_CORRECT is not set, -perm +zzz is treated just like -perm /zzz if +zzz is not a valid symbolic mode.

When POSIXLY_CORRECT is set, such constructs are treated as an error.

When POSIXLY_CORRECT is set, the response to the prompt made by the -ok action is interpreted according to the

system's message catalogue, as opposed to according to find's own message translations.

TZ Affects the time zone used for some of the time-related format directives of -printf and -fprintf.Find Command Examples

find /tmp -name core -type f -print | xargs /bin/rm -fFind files named core in or below the directory /tmp and delete them. Note that this will work incorrectly if there are any filenames containing newlines, single or double quotes, or spaces.

find /tmp -name core -type f -print0 | xargs -0 /bin/rm -fFind files named core in or below the directory /tmp and delete them, processing filenames in such a way that file or directory names containing single or double quotes, spaces or newlines are correctly handled. The -name test comes before the -type test in order to avoid having to call stat(2) on every file.

find . -type f -exec file '{}' \;Runs `file’ on every file in or below the current directory. Notice that the braces are enclosed in single quote marks to protect them from interpretation as shell script punctuation. The semicolon is similarly protected by the use of a backslash, though single quotes could have been used in that case also.

find / \( -perm -4000 -fprintf /root/suid.txt '%#m %u %p\n' \) , \

\( -size +100M -fprintf /root/big.txt '%-10s %p\n' \)Traverse the filesystem just once, listing setuid files and directories into /root/suid.txt and large files into /root/big.txt.

find $HOME -mtime 0Search for files in your home directory which have been modified in the last twenty-four hours. This command works this way because the time since each file was last modified is divided by 24 hours and any remainder is discarded. That means that to match -mtime 0, a file will have to have a modification in the past which is less than 24 hours ago.

find /sbin /usr/sbin -executable \! -readable -printSearch for files which are executable but not readable.

find . -perm 664Search for files which have read and write permission for their owner, and group, but which other users can read but not write to. Files which meet these criteria but have other permissions bits set (for example if someone can execute the file) will not be matched.

find . -perm -664Search for files which have read and write permission for their owner and group, and which other users can read, without regard to the presence of any extra permission bits (for example the executable bit). This will match a file which has mode 0777, for example.

find . -perm /222Search for files which are writable by somebody (their owner, or their group, or anybody else).

find . -perm /220

find . -perm /u+w,g+w

find . -perm /u=w,g=wAll three of these commands do the same thing, but the first one uses the octal representation of the file mode, and the other two use the symbolic form. These commands all search for files which are writable by either their owner or their group. The files don’t have to be writable by both the owner and group to be matched; either will do.

find . -perm -220

find . -perm -g+w,u+wBoth these commands do the same thing; search for files which are writable by both their owner and their group.

find . -perm -444 -perm /222 \! -perm /111

find . -perm -a+r -perm /a+w \! -perm /a+xThese two commands both search for files that are readable for everybody ( -perm -444 or -perm -a+r), have at least one write bit set ( -perm /222 or -perm /a+w) but are not executable for anybody ( ! -perm /111 and ! -perm /a+x respectively).

cd /source-dir

find . -name .snapshot -prune -o \( \! -name '*~' -print0 \)| cpio -pmd0 /dest-dirThis command copies the contents of /source-dir to /dest-dir, but omits files and directories named .snapshot (and anything in them). It also omits files or directories whose name ends in ~, but not their contents. The construct -prune -o \( … -print0 \) is quite common. The idea here is that the expression before -prune matches things which are to be pruned.

However, the -prune action itself returns true, so the following -o ensures that the right hand side is evaluated only for those directories which didn’t get pruned (the contents of the pruned directories are not even visited, so their contents are irrelevant). The expression on the right hand side of the -o is in parentheses only for clarity. It emphasises that the -print0 action takes place only for things that didn’t have -prune applied to them. Because the default `and’ condition between tests binds more tightly than -o, this is the default anyway, but the parentheses help to show what is going on.

find repo/ \( -exec test -d '{}'/.svn \; -or \

-exec test -d {}/.git \; -or -exec test -d {}/CVS \; \) \

-print -pruneGiven the following directory of projects and their associated SCM administrative directories, perform an efficient search for the projects’ roots:

repo/project1/CVS

repo/gnu/project2/.svn

repo/gnu/project3/.svn

repo/gnu/project3/src/.svn

repo/project4/.gitIn this example, -prune prevents unnecessary descent into directories that have already been discovered (for example we do not search project3/src because we already found project3/.svn), but ensures sibling directories (project2 and project3) are found.

find /tmp -type f,d,lSearch for files, directories, and symbolic links in the directory /tmp passing these types as a comma-separated list (GNU extension), which is otherwise equivalent to the longer, yet more portable:

find /tmp \( -type f -o -type d -o -type l \)EXIT STATUS

find exits with status 0 if all files are processed successfully, greater than 0 if errors occur. This is deliberately a very broad description, but if the return value is non-zero, you should not rely on the correctness of the results of find.

When some error occurs, find may stop immediately, without completing all the actions specified. For example, some starting points may not have been examined or some pending program invocations for -exec … {} + or -execdir … {} + may not have been performed.

SEE ALSO

locate(1), locatedb(5), updatedb(1), xargs(1), chmod(1), fnmatch(3), regex(7), stat(2), lstat(2), ls(1), printf(3), strftime(3), ctime(3)

The full documentation for find is maintained as a Text info manual. If the info and find programs are properly installed at your site, the command info find should give you access to the complete manual.